- >>

- Healthy Adult Studies

- HCP Young Adult

- News

- Article

Scientists have new help finding brain’s nooks and crannies

Like explorers mapping a new planet, scientists probing the brain need every type of landmark they can get. Each mountain, river or forest helps scientists find their way through the intricacies of the human brain.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a new technique that provides rapid access to brain landmarks formerly only available at autopsy. Better brain maps will result, speeding efforts to understand how the healthy brain works and potentially aiding in future diagnosis and treatment of brain disorders, the researchers report in The Journal of Neuroscience Aug. 10.

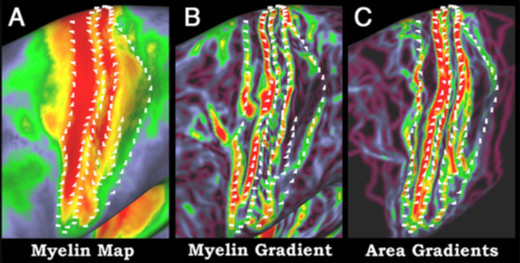

The technique makes it possible for scientists to map myelination, or the degree to which branches of brain cells are covered by a white sheath known as myelin in order to speed up long-distance signaling. It was developed in part through the Human Connectome Project, a $30 million, five-year effort to map the brain’s wiring. That project is headed by Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Minnesota.

“The brain is among the most complex structures known, with approximately 90 billion neurons transmitting information across 150 trillion connections,” says David Van Essen, PhD, Edison Professor and head of the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology at Washington University. “New perspectives are very helpful for understanding this complexity, and myelin maps will give us important insights into where certain parts of the brain end and others begin.”

Easy access to detailed maps of myelination in humans and animals also will aid efforts to understand how the brain evolved and how it works, according to Van Essen.

Neuroscientists have known for more than a century that myelination levels differ throughout the cerebral cortex, the gray outer layer of the brain where most higher mental functions take place. Until now, though, the only way they could map these differences in detail was to remove the brain after death, slice it and stain it for myelin.

Washington University graduate student Matthew Glasser developed the new technique, which combines data from two types of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans that have been available for years.

“These are standard ways of imaging brain anatomy that scientists and clinicians have used for a long time,” Glasser says. “After developing the new technique, we applied it in a detailed analysis of archived brain scans from healthy adults.”

As in prior studies, Glasser’s results show highest myelination levels in areas involved with early processing of information from the eyes and other sensory organs and control of movement. Many brain cells are packed into these regions, but the connections among the cells are less complex. Scientists suspect that these brain regions rely heavily on what computer scientists call parallel processing: Instead of every cell in the region working together on a single complex problem, multiple separate teams of cells work simultaneously on different parts of the problem.

Areas with less myelin include brain regions linked to speech, reasoning and use of tools. These regions have brain cells that are packed less densely, because individual cells are larger and have more complex connections with neighboring cells.

“It’s been widely hypothesized that each chunk of the cerebral cortex is made up of very uniform information-processing machinery,” Van Essen says. “But we’re now adding to a picture of striking regional differences that are important for understanding how the brain works.”

According to Van Essen, the technique will make it possible for the Connectome project to rapidly map myelination in many different research participants. Data on many subjects, acquired through many different analytical techniques including myelination mapping, will help the resulting maps cover the range of anatomic variation present in humans.

“Our colleagues are clamoring to make use of this approach because it’s so helpful for figuring out where you are in the cortex, and the data are either already there or can be obtained in less than 10 minutes of MRI scanning,” Glasser says.

Note: This article by Michael Purdy was reprinted from the Washington University Record. A PDF download of Glasser and Van Essen’s full paper is available to download on our HCP Publications page.